Convolution

A convolution model requires both the evaluation grid and the data to convolve. Examples include using a point-spread function (PSF) model to modify a two-dimensional model to account for blurring due to the instrument (or other sources, such as the atmosphere for ground-based Astronomical data sets), or the redistribution of the counts as a function of energy as modelled by the RMF when analyzing astronomical X-ray spectra.

Note

In the following documentation we are going to use the term “convolution” to refer to any model that requires the data from another model, such as a model that reprocesses emission into another passband or that renormalises the data, even if it does not match the meaning of convolution.

Creating a convolution kernel

For convolution-style models, there are normally two steps to create a model component:

create an instance of the convolution kernel

apply the instance to the model components

The convolution kernel is not an instance of

sherpa.models.model.ArithmeticModel, and so

can not be evaluated by passing it the data grid. Instead,

the kernel is used to wrap another model expression,

normally done by passing the model to be wrapped as the

argument to the model, and the result of this is then

a model that can be evaluated on the data grid.

Note

Evaluating the kernel - such as psf in the example

below - with a grid will raise an error like:

ModelErr: attempted to create ArithmeticFunctionModel from non-callable object of type ndarray

One-dimensional convolution with a PSF

In this example we want to convolve a model by the “kernel”

[5, 10, 3, 2], which requires creating a

sherpa.data.Data1D instance to store the

data, and then pass it to sherpa.instrument.PSFModel:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> from sherpa.data import Data1D

>>> from sherpa.instrument import PSFModel

>>> k = np.asarray([5, 10, 3, 2])

>>> x = np.arange(k.size)

>>> kernel = Data1D('kdata1', x, k)

>>> psf1 = PSFModel('psf1', kernel=kernel)

>>> print(psf1)

psf1

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

psf1.kernel frozen kdata1

psf1.radial frozen 0 0 1

psf1.norm frozen 1 0 1

To show how this model works we will use it to convolve

a Box1D model (this is chosen

since it has sharp edges and so the convolution is more obvious).

>>> from sherpa.models.basic import Box1D

>>> point = Box1D('pt')

>>> point.xlow = 9.5

>>> point.xhi = 10.5

>>> print(point)

pt

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

pt.xlow thawed 9.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.xhi thawed 10.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ampl thawed 1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

The convolution case is created by applying the psf1 model

to the point model (the 2D example

below shows an example of applying a kernel to a

composite model):

>>> convolved = psf1(point)

>>> print(convolved)

psf1(pt)

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

pt.xlow thawed 9.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.xhi thawed 10.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ampl thawed 1 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

The model can be evaluated both before and after convolution, by

passing it the data grid. Unlike normal model evaluation the

PSFModel class requires that its

fold() model be called before

evaluation. This method pre-calculates terms needed for the

convolution (which is done using a fourier transform), and so needs

the grid over which it is to be applied. This is done by passing in a

Data instance (in this case the Y data in the

Data1D instance is not used so is set to

zero):

>>> x = np.arange(6, 15)

>>> blank = Data1D('blank', x, np.zeros(x.size))

>>> psf1.fold(blank)

With this out of the way, we can compare the convolved to un-convolved resuls:

>>> y1 = point(x)

>>> y2 = convolved(x)

>>> for z in zip(x, y1, y2):

... print("x: {:2d} y: {:.0f} convolved: {:.2f}".format(*z))

x: 6 y: 0 convolved: 0.00

x: 7 y: 0 convolved: 0.00

x: 8 y: 0 convolved: 0.00

x: 9 y: 0 convolved: 0.25

x: 10 y: 1 convolved: 0.50

x: 11 y: 0 convolved: 0.15

x: 12 y: 0 convolved: 0.10

x: 13 y: 0 convolved: 0.00

x: 14 y: 0 convolved: 0.00

The PSFModel instance has automatically

selected the largest pixel in the kernel as the center (in this case

the second element, 10), and has automatically re-normalized the

kernel. The parameters of the convolution kernel (in this case

psf1) can be changed to control the behavior.

>>> print(psf1)

psf1

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

psf1.kernel frozen kdata1

psf1.size frozen 4 4 4

psf1.center frozen 2 2 2

psf1.radial frozen 0 0 1

psf1.norm frozen 1 0 1

Note

The model parameters for the convolution kernel have changed

since earlier, as the use of the

fold() method has added

new parameters (in this case the size and center

parameters).

Two-dimensional convolution with a PSF

The sherpa.astro.instrument.PSFModel class augments the

behavior of sherpa.instrument.PSFModel by supporting

images with a World Coordinate System (WCS). For this example

we do not need this capability and so use the

sherpa.instrument.PSFModel class directly.

Including a PSF in a model expression

The “kernel” of the PSF is the actual data used to represent the

blurring, and can be given as a numeric array or as a Sherpa model.

In the following example a simple 3 by 3 array is used to represent

the PSF, but it first has to be converted into a

Data2D object (this is similar to

the steps needed in the

1D case above):

>>> from sherpa.data import Data2D

>>> from sherpa.instrument import PSFModel

>>> k = np.asarray([[0, 1, 0], [1, 0, 1], [0, 1, 0]])

>>> yg, xg = np.mgrid[:3, :3]

>>> kernel = Data2D('kdata', xg.flatten(), yg.flatten(), k.flatten(),

... shape=k.shape)

>>> psf = PSFModel(kernel=kernel)

>>> print(psf)

psfmodel

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

psfmodel.kernel frozen kdata

psfmodel.radial frozen 0 0 1

psfmodel.norm frozen 1 0 1

As shown below, the data in the

PSF is renormalized so that its sum matches the norm parameter,

which here is set to 1.

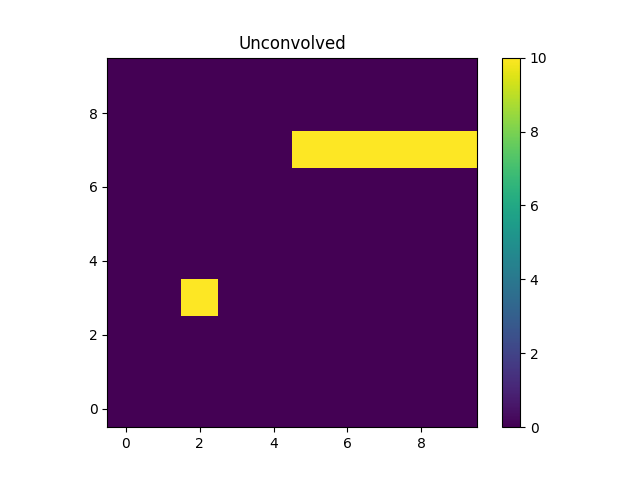

The following example sets up a simple model expression which represents

the sum of a single pixel and a line of pixels, using

Box2D for both.

>>> from sherpa.models.basic import Box2D

>>> pt = Box2D('pt')

>>> pt.xlow, pt.xhi = 1.5, 2.5

>>> pt.ylow, pt.yhi = 2.5, 3.5

>>> pt.ampl = 8

>>> box = Box2D('box')

>>> box.xlow, box.xhi = 4, 10

>>> box.ylow, box.yhi = 6.5, 7.5

>>> box.ampl = 10

>>> unconvolved_mdl = pt + box

>>> print(unconvolved_mdl)

pt + box

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

pt.xlow thawed 1.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.xhi thawed 2.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ylow thawed 2.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.yhi thawed 3.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ampl thawed 8 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.xlow thawed 4 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.xhi thawed 10 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.ylow thawed 6.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.yhi thawed 7.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.ampl thawed 10 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

Note

Although Sherpa provides the Delta2D

class, it is suggested that alternatives such as

Box2D be used instead, since a

delta function is very sensitive to the location at which it

is evaluated. However, including a Box2D component in a fit can still

be problematic since the output of the model does not vary smoothly

as any of the bin edges change, which is a challenge for the

optimisers provided with Sherpa.

Rather than being another term in the model expression - that is, an item that is added, subtracted, multiplied, or divided into an existing expression - the PSF model “wraps” the model it is to convolve. This can be a single model or - as in this case - a composite one:

>>> convolved_mdl = psf(unconvolved_mdl)

>>> print(convolved_mdl)

psfmodel(pt + box)

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

pt.xlow thawed 1.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.xhi thawed 2.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ylow thawed 2.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.yhi thawed 3.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ampl thawed 8 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.xlow thawed 4 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.xhi thawed 10 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.ylow thawed 6.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.yhi thawed 7.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.ampl thawed 10 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

This new expression can be treated as any other Sherpa model, which means that we can apply extra terms to it, such as adding a background component that is not affected by the PSF:

>>> from sherpa.models.basic import Const2D

>>> bgnd = Const2D('bgnd')

>>> bgnd.c0 = 0.25

>>> print(convolved_mdl + bgnd)

psfmodel(pt + box) + bgnd

Param Type Value Min Max Units

----- ---- ----- --- --- -----

pt.xlow thawed 1.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.xhi thawed 2.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ylow thawed 2.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.yhi thawed 3.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

pt.ampl thawed 8 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.xlow thawed 4 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.xhi thawed 10 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.ylow thawed 6.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.yhi thawed 7.5 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

box.ampl thawed 10 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

bgnd.c0 thawed 0.25 -3.40282e+38 3.40282e+38

In the following this extra term (bgnd) is not included to simplify

the comparison between the unconvolved and convolved versions.

Evaluating a model including a PSF

The PSF-convolved model can be evaluated - in most cases - just as is done for ordinary models. That is by supplying it with the grid coordinates to use. However, the need to convolve the data with a fixed grid does limit this somewhat.

For this example, a grid covering the points 0 to 9 inclusive is used for each axis (with a unit pixel size), which means that the unconvolved model can be evaluated with the following:

>>> yg, xg = np.mgrid[:10, :10]

>>> xg1d, yg1d = xg.flatten(), yg.flatten()

>>> m1 = unconvolved_mdl(xg1d, yg1d).reshape(xg.shape)

An easier alternative, once the PSF is included, is to create an

empty dataset with the given grid (that is, a dataset for which we

do not care about the dependent axis), and use the

eval_model() method to

evaluate the model (the result for m1 is the same whichever

approach is used):

>>> blank = Data2D('blank', xg1d, yg1d, np.ones(xg1d.shape), xg.shape)

>>> m1 = blank.eval_model(unconvolved_mdl).reshape(xg.shape)

The “point source” is located at x = 2, y = 3 and the line

starts at x=5 and extends to the end of the grid (at y=7).

Note

In this example the image coordinates were chosen to be the same

as those drawn by matplotlib. The extent parameter of the

imshow call can be used when this correspondance does not

hold.

As with the 1D case, the

fold() method must be called

before evaluation.

>>> psf.fold(blank)

>>> m2 = blank.eval_model(convolved_mdl).reshape(xg.shape)

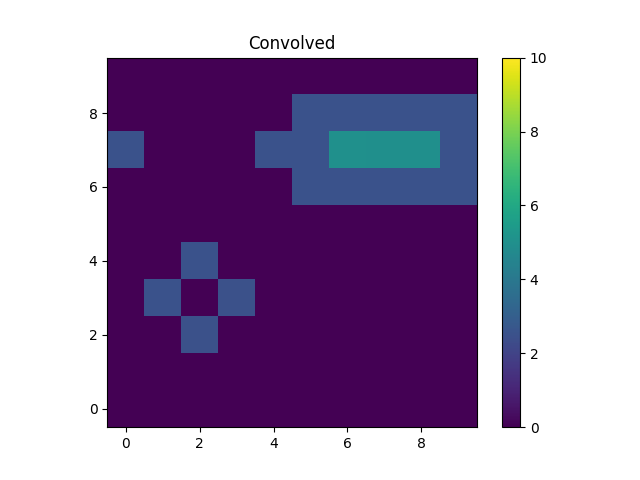

The kernel used redistributes flux from the central pixel to its four

immediate neighbors equally, which is what has happened to the point

source at (2, 2). The result for the line is to blur the line

slightly, but note that the convolution has “wrapped around”, so that

the flux that should have been placed into the pixel at (10, 7),

which is off the grid, has been moved to (0, 7).

Note

If the fold method is not called then evaluating the model will

raise the following exception:

PSFErr: PSF model has not been folded

Care must be taken to ensure that fold is called whenever the grid

has changed. This suggests that the same PSF model should not be used

in simultaneous fits, unless it is known that the grid is the same

in the multiple datasets.

The PSF Normalization

Since the norm parameter of the PSF model was set to 1, the PSF

convolution is flux preserving, even at the edges thanks to the

wrap-around behavior of the fourier transform. This can be seen by

comparing the signal in the unconvolved and convolved images, which

are (to numerical precision) the same:

>>> m1.sum()

58.0

>>> m2.sum()

58.0

The use of a fourier transform means that low-level signal will be

found in many pixels which would expect to be 0. For example,

looking at the row of pixels at y = 7 gives:

>>> m2[7]

array([2.50000000e+00, 1.73472348e-16, 5.20417043e-16, 4.33680869e-16,

2.50000000e+00, 2.50000000e+00, 5.00000000e+00, 5.00000000e+00,

5.00000000e+00, 2.50000000e+00])